The Chemical History of a Candle

Lecture I.

A Candle: The Flame—Its Sources—Structure—Mobility—Brightness

I PURPOSE, in return for the honor you do us by coming to see what are our proceedings here, to bring before you, in the course of these lectures, the Chemical History of a Candle. I have taken this subject on a former occasion, and, were it left to my own will, I should prefer to repeat it almost every year, so abundant is the interest that attaches itself to the subject, so wonderful are the varieties of outlet which it offers into the various departments of philosophy. There is not a law under which any part of this universe is governed which does not come into play and is touched upon in these phenomena. There is no better, there is no more open door by which you can enter into the study of natural philosophy than by considering the physical phenomena of a candle. I trust, therefore, I shall not disappoint you in choosing this for my subject rather than any newer topic, which could not be better, were it even so good.

And, before proceeding, let me say this also: that, though our subject be so great, and our intention that of treating it honestly, seriously, and philosophically, yet I mean to pass away from all those who are seniors among us. I claim the privilege of speaking to juveniles as a juvenile myself. I have done so on former occasions, and, if you please, I shall do so again. And, though I stand here with the knowledge of having the words I utter given to the world, yet that shall not deter me from speaking in the same familiar way to those whom I esteem nearest to me on this occasion.

And now, my boys and girls, I must first tell you of what candles are made. Some are great curiosities. I have here some bits of timber, branches of trees particularly famous for their burning. And here you see a piece of that very curious substance, taken out of some of the bogs in Ireland, called candle-wood; a hard, strong, excellent wood, evidently fitted for good work as a register of force, and yet, withal, burning so well that where it is found they make splinters of it, and torches, since it burns like a candle, and gives a very good light indeed. And in this wood we have one of the most beautiful illustrations of the general nature of a candle that I can possibly give. The fuel provided, the means of bringing that fuel to the place of chemical action, the regular and gradual supply of air to that place of action—heat and light—all produced by a little piece of wood of this kind, forming, in fact, a natural candle.

But we must speak of candles as they are in commerce. Here are a couple of candles commonly called dips. They are made of lengths of cotton cut off, hung up by a loop, dipped into melted tallow, taken out again and cooled, then redipped, until there is an accumulation of tallow round the cotton. In order that you may have an idea of the various characters of these candles, you see these which I hold in my hand—they are very small and very curious. They are, or were, the candles used by the miners in coal mines. In olden times the miner had to find his own candles, and it was supposed that a small candle would not so soon set fire to the fire-damp in the coal mines as a large one; and for that reason, as well as for economy’s sake, he had candles made of this sort—20, 30, 40, or 60 to the pound. They have been replaced since then by the steel-mill, and then by the Davy lamp, and other safety lamps of various kinds. I have here a candle that was taken out of the Royal George [1], it is said, by Colonel Pasley. It has been sunk in the sea for many years, subject to the action of salt water. It shows you how well candles may be preserved; for, though it is cracked about and broken a great deal, yet when lighted it goes on burning regularly, and the tallow resumes its natural condition as soon as it is fused.

Mr. Field, of Lambeth, has supplied me abundantly with beautiful illustrations of the candle and its materials; I shall therefore now refer to them. And, first, there is the suet—the fat of the ox—Russian tallow, I believe, employed in the manufacture of these dips, which Gay-Lussac, or some one who intrusted him with his knowledge, converted into that beautiful substance, stearin, which you see lying beside it. A candle, you know, is not now a greasy thing like an ordinary tallow candle, but a clean thing, and you may almost scrape off and pulverize the drops which fall from it without soiling any thing. This is the process he adopted [2]: The fat or tallow is first boiled with quick-lime, and made into a soap, and then the soap is decomposed by sulphuric acid, which takes away the lime, and leaves the fat rearranged as stearic acid, while a quantity of glycerin is produced at the same time. Glycerin—absolutely a sugar, or a substance similar to sugar—comes out of the tallow in this chemical change. The oil is then pressed out of it; and you see here this series of pressed cakes, showing how beautifully the impurities are carried out by the oily part as the pressure goes on increasing, and at last you have left that substance, which is melted, and cast into candles as here represented. The candle I have in my hand is a stearin candle, made of stearin from tallow in the way I have told you. Then here is a sperm candle, which comes from the purified oil of the spermaceti whale. Here, also, are yellow beeswax and refined beeswax, from which candles are made. Here, too, is that curious substance called paraffine, and some paraffine candles, made of paraffine obtained from the bogs of Ireland. I have here also a substance brought from Japan since we have forced an entrance into that out-of-the-way place—a sort of wax which a kind friend has sent me, and which forms a new material for the manufacture of candles.

And how are these candles made? I have told you about dips, and I will show you how moulds are made. Let us imagine any of these candles to be made of materials which can be cast. “Cast!” you say. “Why, a candle is a thing that melts, and surely if you can melt it you can cast it.” Not so. It is wonderful, in the progress of manufacture, and in the consideration of the means best fitted to produce the required result, how things turn up which one would not expect beforehand. Candles can not always be cast. A wax candle can never be cast. It is made by a particular process which I can illustrate in a minute or two, but I must not spend much time on it. Wax is a thing which, burning so well, and melting so easily in a candle, can not be cast. However, let us take a material that can be cast. Here is a frame, with a number of moulds fastened in it. The first thing to be done is to put a wick through them. Here is one—a plaited wick, which does not require snuffing [3]—supported by a little wire. It goes to the bottom, where it is pegged in—the little peg holding the cotton tight, and stopping the aperture so that nothing fluid shall run out. At the upper part there is a little bar placed across, which stretches the cotton and holds it in the mould. The tallow is then melted, and the moulds are filled. After a certain time, when the moulds are cool, the excess of tallow is poured off at one corner, and then cleaned off altogether, and the ends of the wick cut away. The candles alone then remain in the mould, and you have only to upset them, as I am doing, when out they tumble, for the candles are made in the form of cones, being narrower at the top than at the bottom: so that, what with their form and their own shrinking, they only need a little shaking, and out they fall. In the same way are made these candles of stearin and of paraffine. It is a curious thing to see how wax candles are made. A lot of cottons are hung upon frames, as you see here, and covered with metal tags at the ends to keep the wax from covering the cotton in those places. These are carried to a heater, where the wax is melted. As you see, the frames can turn round; and, as they turn, a man takes a vessel of wax and pours it first down one, and then the next, and the next, and so on. When he has gone once round, if it is sufficiently cool, he gives the first a second coat, and so on until they are all of the required thickness. When they have been thus clothed, or fed, or made up to that thickness, they are taken off and placed elsewhere. I have here, by the kindness of Mr. Field, several specimens of these candles. Here is one only half-finished. They are then taken down and well rolled upon a fine stone slab, and the conical top is moulded by properly shaped tubes, and the bottoms cut off and trimmed. This is done so beautifully that they can make candles in this way weighing exactly four or six to the pound, or any number they please.

We must not, however, take up more time about the mere manufacture, but go a little farther into the matter. I have not yet referred you to luxuries in candles (for there is such a thing as luxury in candles). See how beautifully these are colored; you see here mauve, magenta, and all the chemical colors recently introduced, applied to candles. You observe, also, different forms employed. Here is a fluted pillar most beautifully shaped; and I have also here some candles sent me by Mr. Pearsall, which are ornamented with designs upon them, so that, as they burn, you have, as it were, a glowing sun above, and bouquet of flowers beneath. All, however, that is fine and beautiful is not useful. These fluted candles, pretty as they are, are bad candles; they are bad because of their external shape. Nevertheless, I show you these specimens, sent to me from kind friends on all sides, that you may see what is done and what may be done in this or that direction; although, as I have said, when we come to these refinements, we are obliged to sacrifice a little in utility.

Now as to the light of the candle. We will light one or two, and set them at work in the performance of their proper functions. You observe a candle is a very different thing from a lamp. With a lamp you take a little oil, fill your vessel, put in a little moss or some cotton prepared by artificial means, and then light the top of the wick. When the flame runs down the cotton to the oil, it gets extinguished, but it goes on burning in the part above. Now I have no doubt you will ask how it is that the oil which will not burn of itself gets up to the top of the cotton, where it will burn. We shall presently examine that; but there is a much more wonderful thing about the burning of a candle than this. You have here a solid substance with no vessel to contain it; and how is it that this solid substance can get up to the place where the flame is? How is it that this solid gets there, it not being a fluid? or, when it is made a fluid, then how is it that it keeps together? This is a wonderful thing about a candle.

We have here a good deal of wind, which will help us in some of our illustrations, but tease us in others; for the sake, therefore, of a little regularity, and to simplify the matter, I shall make a quiet flame, for who can study a subject when there are difficulties in the way not belonging to it? Here is a clever invention of some costermonger or street-stander in the market-place for the shading of their candles on Saturday nights, when they are selling their greens, or potatoes, or fish. I have very often admired it. They put a lamp-glass round the candle, supported on a kind of gallery, which clasps it, and it can be slipped up and down as required. By the use of this lamp-glass, employed in the same way, you have a steady flame, which you can look at, and carefully examine, as I hope you will do, at home.

You see, then, in the first instance, that a beautiful cup is formed. As the air comes to the candle, it moves upward by the force of the current which the heat of the candle produces, and it so cools all the sides of the wax, tallow, or fuel as to keep the edge much cooler than the part within; the part within melts by the flame that runs down the wick as far as it can go before it is extinguished, but the part on the outside does not melt. If I made a current in one direction, my cup would be lop-sided, and the fluid would consequently run over; for the same force of gravity which holds worlds together holds this fluid in a horizontal position, and if the cup be not horizontal, of course the fluid will run away in guttering. You see, therefore, that the cup is formed by this beautifully regular ascending current of air playing upon all sides, which keeps the exterior of the candle cool. No fuel would serve for a candle which has not the property of giving this cup, except such fuel as the Irish bogwood, where the material itself is like a sponge and holds its own fuel. You see now why you would have had such a bad result if you were to burn these beautiful candles that I have shown you, which are irregular, intermittent in their shape, and can not, therefore, have that nicely-formed edge to the cup which is the great beauty in a candle. I hope you will now see that the perfection of a process—that is, its utility—is the better point of beauty about it. It is not the gest looking thing, but the best acting thing, which is the most advantageous to us. This good-looking candle is a bad-burning one. There will be a guttering round about it because of the irregularity of the stream of air and the badness of the cup which is formed thereby. You may see some pretty examples (and I trust you will notice these instances) of the action of the ascending current when you have a little gutter run down the side of a candle, making it thicker there than it is elsewhere. As the candle goes on burning, that keeps its place and forms a little pillar sticking up by the side, because, as it rises higher above the rest of the wax or fuel, the air gets better round it, and it is more cooled and better able to resist the action of the heat at a little distance. Now the greatest mistakes and faults with regard to candles, as in many other things, often bring with them instruction which we should not receive if they had not occurred. We come here to be philosophers, and I hope you will always remember that whenever a result happens, especially if it be new, you should say, “What is the cause? Why does it occur?” and you will, in the course of time, find out the reason.

Then there is another point about these candles which will answer a question—that is, as to the way in which this fluid gets out of the cup, up the wick, and into the place of combustion. You know that the flames on these burning wicks in candles made of beeswax, stearin, or spermaceti, do not run down to the wax or other matter, and melt it all away, but keep to their own right place. They are fenced off from the fluid below, and do not encroach on the cup at the sides. I can not imagine a more beautiful example than the condition of adjustment under which a candle makes one part subserve to the other to the very end of its action. A combustible thing like that, burning away gradually, never being intruded upon by the flame, is a very beautiful sight, especially when you come to learn what a vigorous thing flame is—what power it has of destroying the wax itself when it gets hold of it, and of disturbing its proper form if it come only too near.

But how does the flame get hold of the fuel? There is a beautiful point about that—capillary attraction [4]. “Capillary attraction!” you say—”the attraction of hairs.” Well, never mind the name; it was given in old times, before we had a good understanding of what the real power was. It is by what is called capillary attraction that the fuel is conveyed to the part where combustion goes on, and is deposited there, not in a careless way, but very beautifully in the very midst of the centre of action, which takes place around it. Now I am going to give you one or two instances of capillary attraction. It is that kind of action or attraction which makes two things that do not dissolve in each other still hold together. When you wash your hands, you wet them thoroughly; you take a little soap to make the adhesion better, and you find your hands remain wet. This is by that kind of attraction of which I am about to speak. And, what is more, if your hands are not soiled (as they almost always are by the usages of life), if you put your finger into a little warm water, the water will creep a little way up the finger, though you may not stop to examine it. I have here a substance which is rather porous—a column of salt—and I will pour into the plate at the bottom, not water, as it appears, but a saturated solution of salt which can not absorb more, so that the action which you see will not be due to its dissolving any thing. We may consider the plate to be the candle, and the salt the wick, and this solution the melted tallow. (I have colored the fluid, that you may see the action better.) You observe that, now I pour in the fluid, it rises and gradually creeps up the salt higher and higher (Fig. 1); and provided the column does not tumble over, it will go to the top. If this blue solution were combustible, and we were to place a wick at the top of the salt, it would burn as it entered into the wick. It is a most curious thing to see this kind of action taking place, and to observe how singular some of the circumstances are about it. When you wash your hands, you take a towel to wipe off the water; and it is by that kind of wetting, or that kind of attraction which makes the towel become wet with water, that the wick is made wet with the tallow. I have known some careless boys and girls (indeed, I have known it happen to careful people as well) who, having washed their hands and wiped them with a towel, have thrown the towel over the side of the basin, and before long it has drawn all the water out of the basin and conveyed it to the floor, because it happened to be thrown over the side in such a way as to serve the purpose of a siphon [5]. That you may the better see the way in which the substances act one upon another, I have here a vessel made of wire gauze filled with water, and you may compare it in its action to the cotton in one respect, or to a piece of calico in the other. In fact, wicks are sometimes made of a kind of wire gauze. You will observe that this vessel is a porous thing; for if I pour a little water on to the top, it will run out at the bottom. You would be puzzled for a good while if I asked you what the state of this vessel is, what is inside it, and why it is there? The vessels is full of water, and yet you see the water goes in and runs out as if it were empty. In order to prove this to you, I have only to empty it. The reason is this: the wire, being once wetted, remains wet; the meshes are so small that the fluid is attracted so strongly from the one side to the other, as to remain in the vessel, although it is porous. In like manner, the particles of melted tallow ascend the cotton and get to the top: other particles then follow by their mutual attraction for each other, and as they reach the flame they are gradually burned.

Here is another application of the same principle. You see this bit of cane. I have seen boys about the streets, who are very anxious to appear like men, take a piece of cane, and light it, and smoke it, as an imitation of a cigar. They are enable to do so by the permeability of the cane in one direction, and by its capillarity. If I place this piece of cane on a plate containing some camphene (which is very much like paraffine in its general character), exactly in the same manner as the blue fluid rose through the salt will this fluid rise through the piece of cane. There being no pores at the side, the fluid can not go in that direction, but must pass through its length. Already the fluid is at the top of the cane; now I can light it and make it serve as a candle. The fluid has risen by the capillary attraction of the piece of cane, just as it does through the cotton in the candle.

Now the only reason why the candle does not burn all down the side of the wick is that the melted tallow extinguishes the flame. You know that a candle, if turned upside down, so as to allow the fuel to run upon the wick, will be put out. The reason is, that the flame has not had time to make the fuel hot enough to burn, as it does above, where it is carried in small quantities into the wick, and has all the effect of the heat exercised upon it.

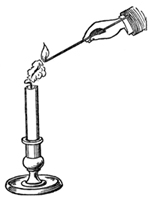

There is another condition which you must learn as regards the candle, without which you would not be able fully to understand the philosophy of it, and that is the vaporous condition of the fuel. In order that you may understand that, let me show you a very pretty but very commonplace experiment. If you blow a candle out cleverly, you will see the vapor rise from it. You have, I know, often smelt the vapor of a blown-out candle, and a very bad smell it is; but if you blow it out cleverly you will be able to see pretty well the vapor into which this solid matter is transformed. I will blow out one of these candles in such a way as not to disturb the air around it by the continuing action of my breath; and now, if I hold a lighted taper two or three inches from the wick, you will observe a train of fire going through the air till it reaches the candle (Fig. 2). I am obliged to be quick and ready, because if I allow the vapor time to cool, it becomes condensed into a liquid or solid, or the stream of combustible matter gets disturbed.

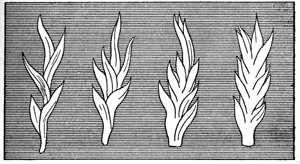

Now as to the shape or form of the flame. It concerns us much to know about the condition which the matter of the candle finally assumes at the top of the wick, where you have such beauty and brightness as nothing but combustion or flame can produce. You have the glittering beauty of gold and silver, and the still higher lustre of jewels like the ruby and diamond; but none of these rival the brilliancy and beauty of flame. What diamond can shine like flame? It owes its lustre at nighttime to the very flame shining upon it. The flame shines in darkness, but the light which the diamond has is as nothing until the flame shines upon it, when it is brilliant again. The candle alone shines by itself and for itself, or for those who have arranged the materials. Now let us look a little at the form of the flame as you see it under the glass shade. It is steady and equal, and its general form is that which is represented in the diagram (Fig. 3), varying with atmospheric disturbances, and also varying according to the size of the candle. It is a bright oblong, brighter at the top than toward the bottom, with the wick in the middle, and, besides the wick in the middle, certain darker parts towards the bottom, where the ignition is not so perfect as in the part above. I have a drawing here, sketched many years ago by Hooker, when he made his investigations. It is the drawing of the flame of a lamp, but it will apply to the flame of a candle. The cup of the candle is the vessel or lamp; the melted spermaceti is the oil; and the wick is common to both. Upon that he sets this little flame, and then he represents what is true, a certain quantity of matter rising about it which you do not see, and which, if you have not been here before, or are not familiar with the subject, you will not know of. He has here represented the parts of the surrounding atmosphere that are very essential to the flame, and that are always present with it. There is a current formed, which draws the flame out; for the flame which you see is really drawn out by the current, and drawn upward to a great height, just as Hooker has here shown you by that prolongation of the current in the diagram. You may see this by taking a lighted candle, and putting it in the sun so as to get its shadow thrown on a piece of paper. How remarkable it is that that thing which is light enough to produce shadows of other objects can be made to throw its own shadow on a piece of white paper or card, so that you can actually see streaming round the flame something which is not part of the flame, but is ascending and drawing the flame upward. Now I am going to imitate the sunlight by applying the voltaic battery to the electric lamp. You now see our sun and its great luminosity; and by placing a candle between it and the screen, we get the shadow of the flame. You observe the shadow of the candle and of the wick; then there is a darkish part, as represented in the diagram (Fig. 4), and then a part which is more distinct. Curiously enough, however, what we see in the shadow as the darkest part of the flame is, in reality, the brightest part; and here you see streaming upward the ascending current of hot air, as shown by Hooker, which draws out the flame, supplies it with air, and cools the sides of the cup of melted fuel.

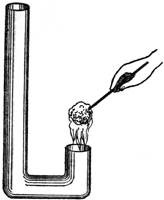

I can give you here a little farther illustration, for the purpose of showing you how flame goes up or down according to the current. I have here a flame—it is not a candle flame—but you can, no doubt, by this time generalize enough to be able to compare one thing with another. What I am about to do is to change the ascending current that takes the flame upward into a descending current. This I can easily do by the little apparatus you see before me. The flame, as I have said, is not a candle flame, but it is produced by alcohol, so that it shall not smoke too much. I will also color the flame with another substance [6], so that you may trace its course; for, with the spirit alone, you could hardly see well enough to have the opportunity of tracing its direction. By lighting this spirit of wine we have then a flame produced, and you observe that when held in the air it naturally goes upward. You understand now, easily enough, why flames go up under ordinary circumstances: it is because of the draught of air by which the combustion is formed. But now, by blowing the flame down, you see I am enabled to make it go downward into this little chimney, the direction of the current being changed (Fig. 5). Before we have concluded this course of lectures we shall show you a lamp in which the flame goes up and the smoke goes down, or the flame goes down and the smoke goes up. You see, then, that we have the power in this way of varying the flame in different directions.

There are now some other points that I must bring before you. Many of the flames you see here vary very much in their shape by the currents of air blowing around them in different directions; but we can, if we like, make flames so that they will look like fixtures, and we can photograph them—indeed, we have to photograph them—so that they become fixed to us, if we wish to find out every thing concerning them. That, however, is not the only thing I wish to mention. If I take a flame sufficiently large, it does not keep that homogeneous, that uniform condition of shape, but it breaks out with a power of life which is quite wonderful. I am about to use another kind of fuel, but one which is truly and fairly a representative of the wax or tallow of a candle. I have here a large ball of cotton, which will serve as a wick. And, now that I have immersed it in spirit and applied a light to it, in what way does it differ from an ordinary candle? Why, it differs very much in one respect, that we have a vivacity and power about it, a beauty and a life entirely different from the light presented by a candle. You see those fine tongues of flame rising up. You have the same general disposition of the mass of the flame from below upward; but, in addition to that, you have this remarkable breaking out into tongues which you do not perceive in the case of a candle. Now, why is this? I must explain it to you, because, when you understand that perfectly, you will be able to follow me better in what I have to say hereafter. I suppose some here will have made for themselves the experiment I am going to show you. Am I right in supposing that any body here has played at snapdragon? I do not know a more beautiful illustration of the philosophy of flame, as to a certain part of its history, than the game of snapdragon. First, here is the dish; and let me say, that when you play snapdragon properly you ought to have the dish well warmed; you ought also to have warm plums, and warm brandy, which, however, I have not got. When you have put the spirit into the dish, you have the cup and the fuel; and are not the raisins acting like the wicks? I now throw the plums into the dish, and light the spirit, and you see those beautiful tongues of flame that I refer to. You have the air creeping in over the edge of the dish forming these tongues. Why? Because, through the force of the current and the irregularity of the action of the flame, it can not flow in one uniform stream. The air flows in so irregularly that you have what would otherwise be a single image broken up into a variety of forms, and each of these little tongues has an independent existence of its own. Indeed, I might say, you have here a multitude of independent candles. You must not imagine, because you see these tongues all at once, that the flame is of this particular shape. A flame of that shape is never so at any one time. Never is a body of flame, like that which you just saw rising from the ball, of the shape it appears to you. I consists of a multitude of different shapes, succeeding each other so fast that the eye is only able to take cognizance of them all at once. In former times I purposely analyzed a flame of that general character, and the diagram shows you the different parts of which it is composed (Fig. 6). They do not occur all at once; it is only because we see these shapes in such rapid succession that they seem to us to exist all at one time.

It is too bad that we have not got farther than my game of snapdragon; but we must not, under any circumstances, keep you beyond your time. It will be a lesson to me in future to hold you more strictly to the philosophy of the thing than to take up your time so much with these illustrations.

NOTES

Note 1. The Royal George sunk at Spithead on the 29th of August, 1782. Colonel Pasley commenced operations for the removal of the wreck by the explosion of gunpowder, in August 1839. The candle which Professor Faraday exhibited must therefore have been exposed to the action of salt water for upward of fifty-seven years.

Note 2. The fat or tallow consists of a chemical combination of fatty acids with glycerin. The lime unites with the palmitic, oleic, and stearic acids, and separates the glycerin. After washing, the insoluble lime soap is decomposed with hot dilute sulphuric acid. The melted fatty acids thus rise as an oil to the surface, when they are decanted. They are again washed and cast into thin plates, which, when cold, are placed between layers of cocoanut matting and submitted to intense hydraulic pressure. In this way the soft oleic acid is squeezed out, while the hard palmitic and stearic acids remain. These are farther purified by pressure at a higher temperature and washing in warm dilute sulphuric acid, when they are ready to be made into candles. These acids are harder and whiter than the fats from which they were obtained, while at the same time they are cleaner and more combustible.

Note 3. A little borax or phosphorus salt is sometime added in order to make the ash fusible.

Note 4. Capillary attraction or repulsion is the cause which determines the ascent or descent of a fluid in a capillary tube. If a piece of thermometer tubing, open at each end, be plunged into water, the latter will instantly rise in the tube considerably above its external level. If, on the other hand, the tube be plunged into mercury, a repulsion instead of attraction will be exhibited, and the level of the mercury will be lower in the tube than it is outside.

Note 5. The late Duke of Sussex was, we believe, the first to show that a prawn might be washed upon this principle. If the tail, after pulling off the fan part, be placed in a tumbler of water, and the head be allowed to hang over the outside, the water will be sucked up the tail by capillary attraction, and will continue to run out through the head until the water in the glass has sunk so low the tail ceases to dip into it.

Note 6. The alcohol had chloride of copper dissolved in it: this produces a beautiful green flame.